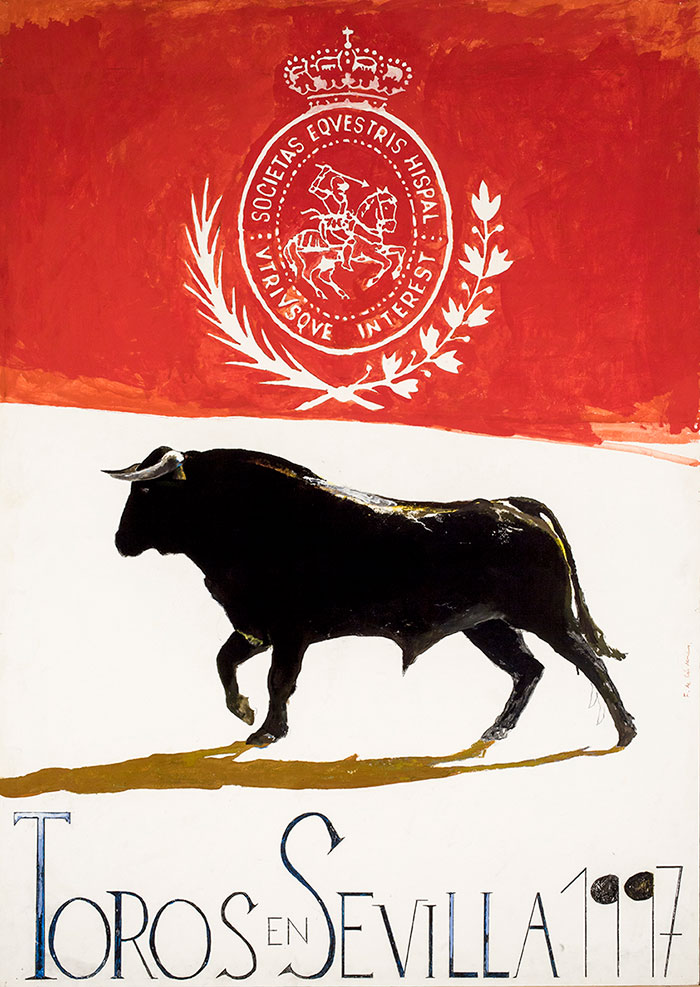

Foto 1997. Cartel de Félix de Cárdenas.

Colección RMCS

The Bull and the Arts

The Bullfighting Festival has been a subject treated by artists of different types in all the expressive disciplines

Bullfighting is not merely a public spectacle, typical of a particular culture or country. Since time immemorial, the bull and everything associated with it have been a source of inspiration in art and therefore in culture.

There are no known representations of living beings that are older than those of the bull. Moreover, the last efforts of the best artistic interpreter of tauromachy, Pablo Picasso, were applied to the effigy of a matador.

The Bullfighting Festival, as we know it in modern times, has been a subject treated by artists of different types in all the expressive disciplines, from the plastic arts to the cinema and literature, both narrative and poetic.

Foto 1997. Cartel de Félix de Cárdenas.

RMCS collection.

Literature

In Spanish literature, the phenomenon of bullfighting appears as a constant presence, but at first in an isolated manner, as if in passing, and it was not used as the central protagonist or main occurrence until the beginning of Romanticism, the period in which bullfighting festivals began to be arranged as regulated and well-organized events, and in which their principal actors, the bullfighters, became popular heroes.

Apart from Nicolás Fernández de Moratín, one of the few XVIIIth century intellectuals who dealt with bullfighting (Oda a Pedro Romero, Carta histórica sobre el origen y progresos de las fiestas de toros en España), Professor Alberto González Troyano drew attention to a singular aspect: “…the role of awakening the potential for argument that is inherent in the world of bullfighting seems to have fallen on foreign romantic writers.”

Stories of love between the hero (the bullfighter) and a lady, in an atmosphere charged with pure breeding, thus became the basis of a large part of the literature associated with bullfighting. Merimée and the bullfighter in his Carmen; El toreador by the Duchess of Abrantes; Militona by Théophile Gautier; Cartucherita by Arturo Reyes and Sangre y Arena by Blasco Ibáñez all provided this essential component, with the addition of a tragic element, the death of the bullfighter in front of his beloved.

In the XXth century, several works by national and foreign authors were published, among which we can highlight three because of their international transcendence: the previously-mentioned Sangre y Arena, by Blasco Ibáñez; Fiesta and Verano sangriento by Ernest Hemingway.

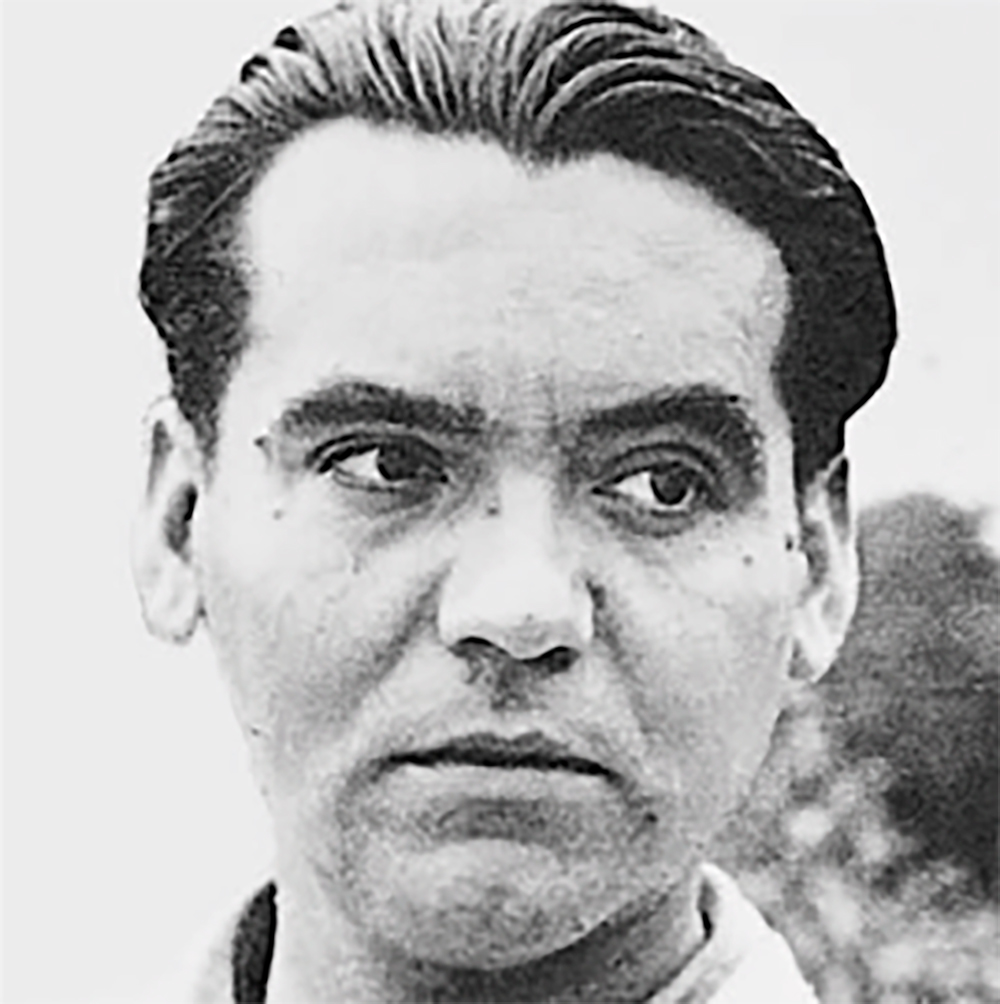

Théophile Gautier

(1811-1872)

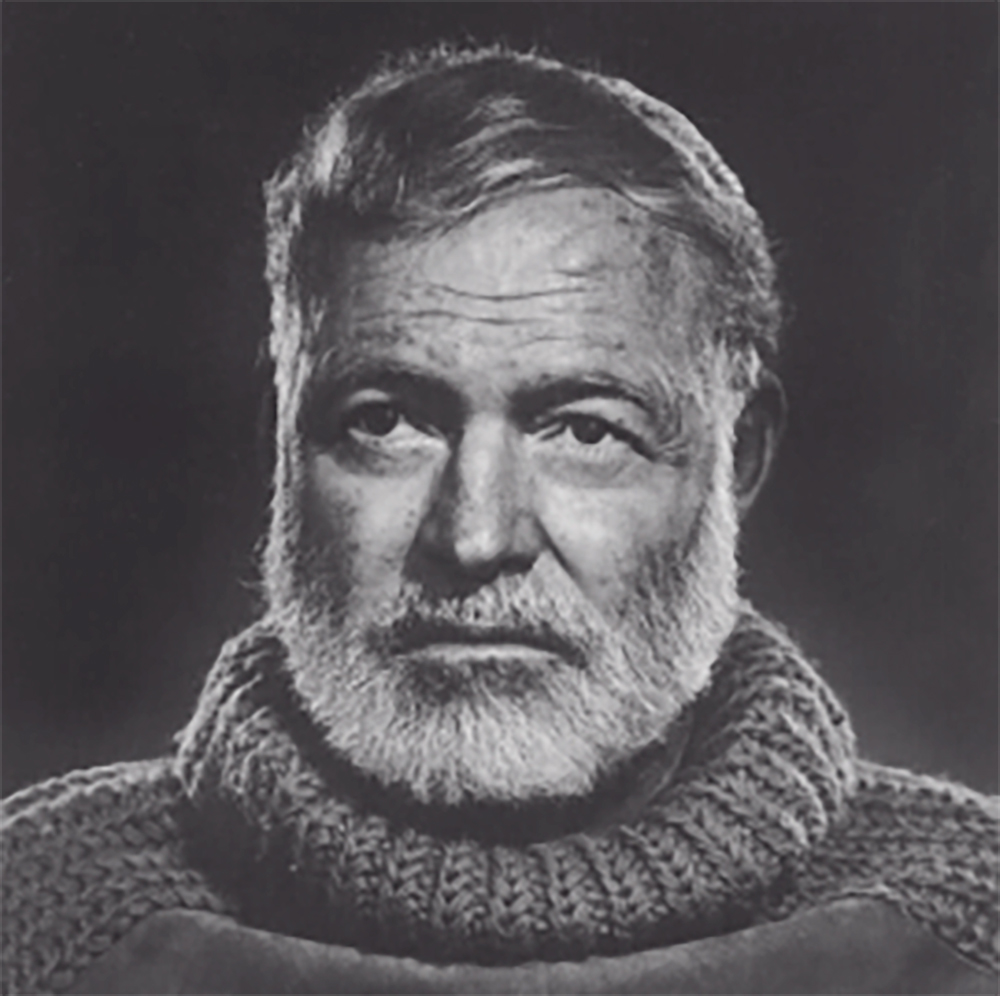

Ernest Hemingway

(1899-1961)

Federico García Lorca

(1898-1936)

“I consider that bullfighting is the most cultured of all the festivals”, wrote Federico García Lorca. The writers of his generation were perhaps the first to consider that bullfighting belonged more to the field of artistic creation. Representative of this proximity is the picture of the members of the Generation of the 27 assembled in Seville round the figure of the bullfighter and patron Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, on whose death Lorca himself wrote one of the most moving poetic elegies of all time. Poets such as Gerardo Diego and Rafael Alberti left numerous proofs of their interest, as did José Bergamín with La música callada del torero, and Vicente Aleixandre, Dámaso Alonso, José María Pemán, Jorge Luis Borges, Miguel Angel Asturias, Pablo Neruda, Jorge Guillén and Jean Cocteau, among others.

Poster from the film directed by F. Niblo and starring Rudolph Valentino, 1922.

Cinema

It is illustrative to review the extensive filmography that has reflected, directly or indirectly, the world of bullfighting. Spanish cinema has been involved with it since the first decade of the XXth century, with titles such as La Otra Carmen (1915) of José de Togores or Sangre y Arena (1916), directed by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez. The best-known versions of Currito de la Cruz (1925) are those of Fernando Delgado and Alejandro Pérez Lugín, of Fernando Delgado himself in 1936, and the 1948 version by Luis Lucía, which is considered the best. Other famous Spanish directors who worked on the theme of bullfighting were Juan de Orduña (Leyenda de Feria, 1945), Edgar Neville (Olé, torero, 1945), Benito Perojo (El traje de luces, 1949), Juan Antonio Bardem (A las cinco de la tarde, 1960), Carlos Saura (Los golfos, 1960), Basilio Martín Patino (El noveno y Torerillos 61, 1961), Jaime de Armiñan (Juncal, 1988, series for TV), Pedro Almodóvar (Matador, 1986), Javier Elorrieta, with another version of Belmonte, 1989, starring Sharon Stone, and Juan Sebastian Bollaín (Sangre y Arena, 1994), to name only some of them, but the list is very long.

The cinema of Hollywood also has bullfighting titles, apart from having such illustrious enthusiasts as Mel Ferrer and Orson Welles. As early as 1915, Cecil B. De Mille directed a version of Carmen, and Fred Niblo shot Sangre y Arena (1922) with Blasco Ibáñez as scriptwriter, and starring Rudolph Valentino, before the arrival of sound. The great Raoul Walsh can be added to the list with The Spaniard (1925), and Robert Mamoulian made a new version of Blasco Ibáñez’s famous work in 1941. The list is long, with directors of the stature of Richard Thorpe, Robert Rossen, Henry King and Budd Boetticher. Moreover, the Mexican film industry, since the Oro, sangre y sol of Miguel Contreras Torres (1925), has also dealt with the festival which is also its own. And in European filmography there is no shortage of titles which directly or indirectly reflect some aspect of bullfighting. Finally, we can mention the co-production Manolete, of Menno Meyjes, starring Adrien Brody and Penelope Cruz in 2006.

Sculpture

In sculpture we find numerous works whose subject is bullfighting. In the introductory text to the exhibition Toros y toreros en la escultura española (1984), sponsored by the BBVA and presented in Madrid by the Real Maestranza de Caballería de Sevilla, its curator Álvaro Martínez-Novillo tells us: “Very soon the unmistakeable sculptural forms of the bull -sacred and virile- will become familiar to the various towns and villages in our Peninsula. Sculptures of bulls such as those in Osuna, Porcuna, Rojales and Monforte. Bronze bulls like the one in Aziala (Teruel). Bulls sculpted in granite by the Celtiberians, like those of Guisando or the magnificent one which guards its homonymous city (Toro), or the bronze bulls of Costix (Balearic Islands).” And he reminds us that the oldest representations of a bullfight could be some small bronzes discovered in the remote Chinese province of Yunan, dating from the Ist century B.C., in which one can see spectators in the tendidos and a bull coming out of a toril.

Related works appeared sporadically during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, reliefs in the cathedrals of Pamplona and Plasencia, and in the University of Salamanca, with horse riders spearing bulls. Before Goya there were no manifestations that were specific to bullfighting festivals. These were the times of Pedro Romero and Costillares. It was precisely those two who were depicted for the first time in the first sculptural group at a bullfight, the polychrome carvings of the sculptor to the Court of Carlos VI and Fernando VII, Pedro Antonio Hermoso from Granada(1763-1830), presumably completed under the direction of Goya.

Iberian bull of Porcuna, VIth century B.C. Limestone.

Museum of Jaén.

Bull of Azaila, IInd century B.C. Bronze.

National Archaeological Museum, Madrid.

Bull of Costitx, IVth-IIIrd century B.C. Bronze.

National Archaeological Museum, Madrid.

Bullfighter, 1913. Manolo Hugué. Stone.

National Art Gallery of Catalonia, Barcelona.

Escultura

During the period of Romanticism, statuettes of bullfighters proliferated, but sculptural production was lower than that of the lithographic series which spread throughout Europe, creating the most picturesque impression of Spain. The first large sculptural group to be dedicated to a bullfighter is that of Francisco Montes Paquiro, created from the bullfighter’s death mask by the royal sculptor José Piquer y Duart (1807-1871).

The Valencian Mariano Benlliure ( 1862-1947) was for bullfighting sculpture what Goya was for bullfighting painting and engraving. The group El Coleo (1911), in the Cuban locality of Guines, impresses by its strength, and the funereal monument to Joselito el Gallo, in the cemetery of Seville, impresses most of all. One of his apprentices, Juan Cristóbal, and Sebastián Miranda, both friends of Belmonte, were great portraitists of bullfighters. Also worthy of mention is J.L. Vasallo ( 1908-1986), who, commissioned by the Real Maestranza de Sevilla, produced likenesses of Rafael el Gallo and of Belmonte, which can be found in its Bullfighting Museum.

The vanguard of the so-called Paris School extended bullfighting sculptural production and gave it a new dimension. Picasso dedicated to the world of the bull more works of another kind, but it is impossible not to mention his Cabeza de toro, formed by a bicycle saddle and handlebars (Museé Picasso, Paris). Outstanding in this field was his friend Manolo Hugué (1872-1945), the great bullfighting sculptor of the vanguard, and Pablo Gargallo (1885-1924) with his work Cabeza de picador (MOMA, New York). In Spain these works influenced artists such as Angel Ferrant (1891-1960) and Alberto Sánchez (1895-1962), to whom one should add Cristino Mallo and Venancio Blanco, son of a cowhand from the herd of Pérez Tabernero, and creator of the statue of Belmonte in Triana.

Tauromachy is now integrated into our sculpture, as has been expressed by artists as distinct as Pablo Serrano and Berrocal, who provided the dimension of their serialized work. Since then, numerous examples have continued to be produced. One of the most recent, and most striking, in which the bull is given prominence, is the work Charging Bull by Arturo di Módica, which is sited in Bowling Green, near Wall Street in New York.

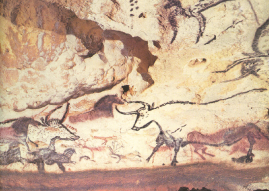

Cave of la Pileta

Benaoján ( Málaga).

Painting

In the first artistic representations of Man on the Earth there are figures of bulls. Pedro Romero de Solís reminds us in one of his studies that from the Cave of La Pileta de la Serranía in Ronda, passing through Lascaux in the Dordogne, to the Grotte de Chauvet in the French Ardèches, 30,000 years ago figures of animals appeared as if miraculously in secret places, inaccessible in the depths of the earth. Among them were figures of bulls which, being the first known paintings created by men, are perhaps the most perfect and beautiful that we know.

Subsequently, under the influence of the civilizations of Egypt and the Orient, a powerful culture was born on the island of Crete, which eventually dominated the Mediterranean. Excavations in Crete brought forth numerous and beautiful representations of the bull and, especially significant, bullfighting scenes that were painted al fresco on the walls of the main patio of the palace of Knossos, which must have served as a bullring. It was there that the half-man, half-bull monster, to which legend gave the name of the Minotaur, was born. Picasso, who knew every detail of the archaeological discoveries in Crete, made this chimera his own and converted it into one of the sources of his pictorial creation.

In the Iberian Peninsula there are many figures of bulls, sculpted by the Iberian peoples from various different materials. Mediaeval and Renaissance art has left evidence of popular bullfighting festivals. In the Baroque period, the nobility became strongly involved with the games with bulls, and bullfighting scenes began to appear in paintings and prints, reflecting the social importance that they had acquired in that period.

After a period of history during which there was a certain ostracism, because of a variety of circumstances both political and social, it was through Goya that the popular form of tauromachy, the one on foot, began to be prominent in pictorial representations. The great blossoming of bullfighting painting in the XIXth century was closely related to the journeys of foreign writers -English and French especially- in Spain, and of the illustrators who frequently accompanied them to reproduce scenes showing the customs of our country. The bullring of the Maestranza de Sevilla would become a model renowned in the world, and many painters depicted their bullfighters fighting there.

The artistic vanguards of the XXth century, typified by Picasso, dealt with the world of bullfighting. It can be claimed that Goya and Picasso represented the highest artistic expression in the interpretation of bullfighting, and were instrumental in giving it a global dimension. Since then, numerous works by contemporary painters have approached this environment. An example of this phenomenon is the emergence of the bullfighting poster in the nineteen twenties, in which competent artists participated, as evidenced today by the poster collection of the Real Maestranza.