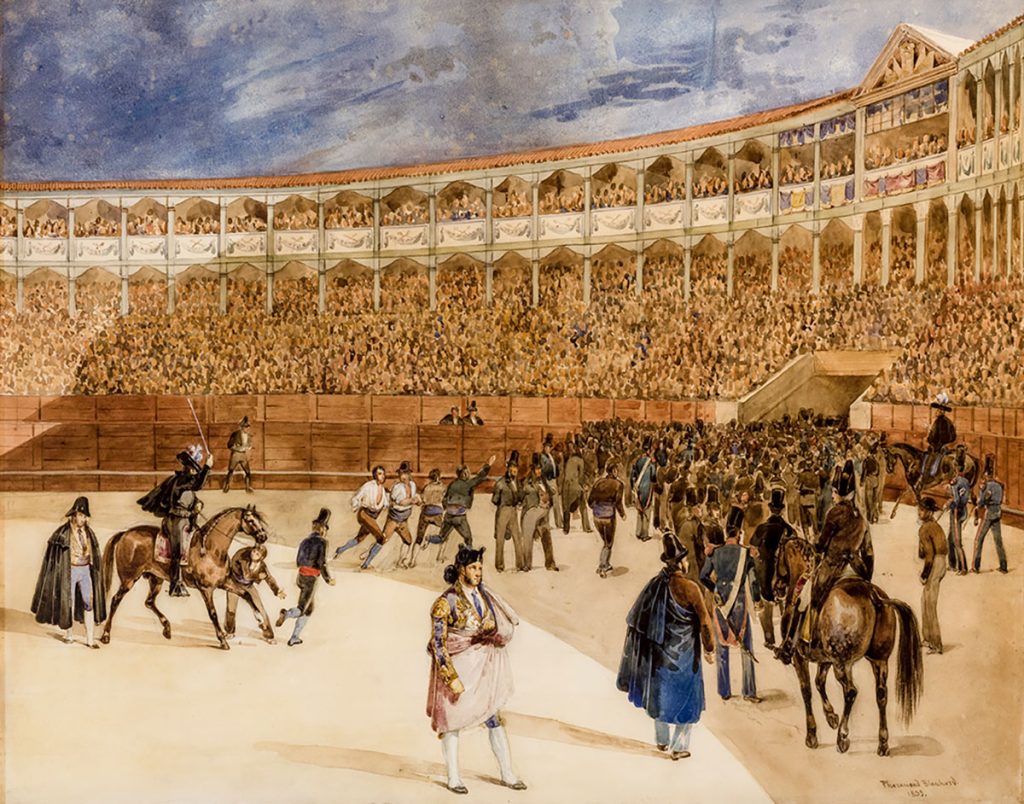

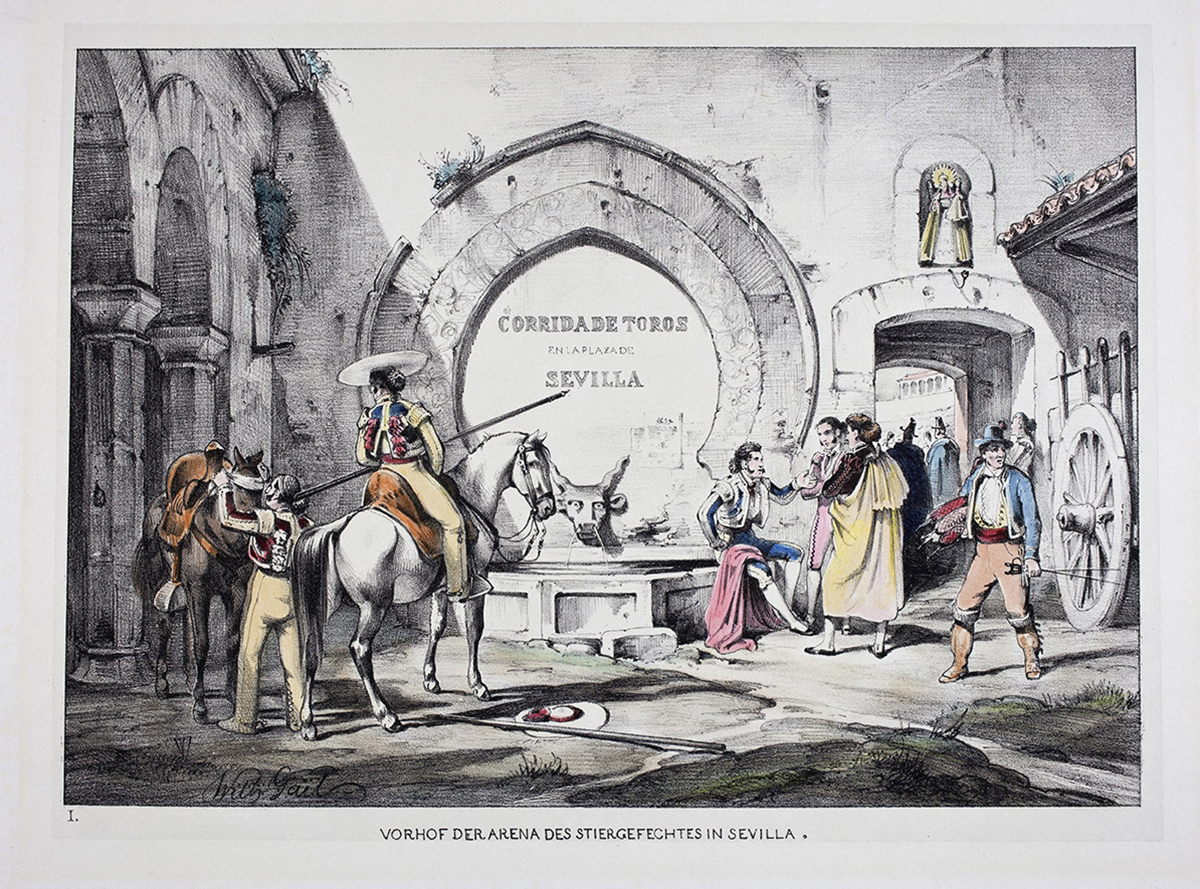

Foto Patio de caballos en la plaza de Sevilla. W. Gaïl, c.1845-37.

Litografía, fondo de color. Colección RMCS.

The Bullfight

Spectacle in which people run in front of several fighting bulls or fight them on foot in an enclosed area constructed for that purpose

“In bullfights, everything is combined: colour, gaiety, tragedy, bravery, talent, brutality, energy and strength, grace, emotion …It is the most complete of all spectacles. From now on, I cannot do without bullfights.”

Charles Chaplin

Statements made to the writer and journalist Tomás Borrás, published in his article of 11 August, 1931, in the ABC newspaper, after the bullfight which Chaplin attended in the San Sebastian bullring…

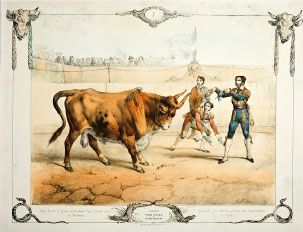

The bullfight is a spectacle in which people run in front of several fighting bulls or fight them on foot in an enclosed area constructed for that purpose, the bullring. It is the oldest mass spectacle in Spain and one of the oldest in the world. In the bullfight, several matadors take part on foot — usually three — assisted by their respective teams, consisting of three banderilleros or peons and two picadores on horseback. In total, twelve bullfighters on foot and six on horseback, who have to fight six bulls. The animals that are fought must be between four and six years old, must have passed a veterinary examination certifying their suitability, and must be killed by swordsmen who have received the alternativa as matador of bulls, that is to say, who are ‘maestros’.

Bullfights which do not fulfil these requirements, or in which the animals have not reached that age, are called novilladas. It is the bullfighters who are responsible for the strict compliance with the Bullfighting Regulations, answering to the authority, the President of the Bullring. They have to execute the different passes in accordance with a set order, and within a limited time. La lidia with each bull is carried out in three successive tercio: the tercio de varas, the tercio de banderillas and the tercio de muerte, and is spread over the area of the bullring which in turn is divided into tablas, the tercio, and the medios which corresponds to the central area of the bullring, but the three successive phases in which the combat unfolds are also called tercio: the tercio de varas, the tercio de banderillas and the tercio de muerte.

At the beginning of the modern tercio de varas, the bull gallops out of the bullpen and the matador normally stops it with the bullfighter’s capote, then moves it towards the picador in order to execute the pass. There follow the distractions of the peons to separate the bull from the horse, which is protected by the pad, and the distraction test, which is normally performed by the matador to test the severity of the punishment. Sometimes, the next matador in the order of the bullfight, to please the spectators or motivated by rivalry, performs an answering distraction, which he has the right, but not the obligation, to perform.

In the course of this third tercio, the matador, armed with the muleta and the sword, prepares the bull so that once it has accepted death, he can finish it off with the thrust, the culminating moment of the la lidia: “There is no paradise without a sword!”, as the bullfighting fans often say. There are three ways of doing it: the old way, in which the matador, immobile, waits for the bull to charge and uses the moment of crossing to plunge the sword in; al volapié, in which the matador, taking advantage of the stillness of the vanquished bull, falls upon the bull’s cross and sinks the sword in; and the encounter, in which matador and bull attack each other simultaneously. The death of the bull is assured, once it has fallen to the ground, by a dagger blow in the nape.

In this tercio the matador exercises his artistic skill in many and different passes with the muleta: pase alto, estatuarios, right-handed passes, chest passes, natural passes with the left hand, circular passes, trincherazos and, completing this series with fancy movements and dodges, notably the long cordobesa and the Belmonte-style al farol. The aficionados demand not only that these passes be executed with calmness, rhythm and control, but also that they should be linked, such that when one pass is finishing, the next in the series is beginning. These series are collectively known as the faena.

Occasionally a matador will try a new pass, which if accepted quickly receives the name of its first exponent: we remember, with the cape, the chicuelinas of the Sevillian bullfighter Chicuelo, and the gaoneras which were performed for the first time by the Mexican matador Rodolfo Gaona and, with the muleta, the manoletinas of the Cordoban Manolete and the bernardinas of the Catalonian Joaquín Bernardó.

The dead bull is dragged out of the arena by galloping mules while the arena workers of the bullring remove the remains of blood from the arena, and in the alley, certain assistants exert themselves to remove all blood from capote, muletas and swords. In every sacrificial ceremony the evidence of violence is hidden. In the few seconds during which the mules remove the bull dispossessed of his life, the spectators collectively express their opinion of the bull: they boo and whistle if it did not please them, and they cheer and applaud if it behaved bravely and nobly.

The President, in recognition of a particular bull’s great bravery, can grant its return to the arena while the spectators, standing, emotionally applaud the animal, whose name will be remembered by the aficionados. Presidents recently received the power to spare the life of a bull that is considered exceptional, in what is termed an indulto. This new vesting of authority is not to the liking of all the devotees because the lower the category of the bullring, the greater the number of reprieves granted. The matador, depending on the spectators’ opinion of the quality of his performance, can receive applause, can salute in the tercio, can go round the arena or can receive, in recognition of his performance, up to two ears. The tearing apart to which the bull is submitted in some bullrings, in which the tail and legs are removed, is merely a proof of their inferior category, and of their spectators’ ignorance about bullfighting.

Historical evolution

Primitive tauromachy. The popular bull: encierros and capeas

The sacrificial game with fighting bulls — a practice that is often festive, but also sometimes beautiful and terrible — has been with us in Spain since time immemorial, as evidenced by the wall paintings of the Spanish Levant: the Spaniards who were natives of any of the various kingdoms that formerly made up their multiple monarchy have always played and sacrificed, and probably always will play with and sacrifice, bulls. But also in Europe, many thousands of years earlier than in Spain, as evidenced by the impressive paintings of the caves of Lascaux and Chauvet, where more than thirty thousand years ago is seen to be linked to the worship of wild bulls.

Since the sensational discovery of the frescos of the palace of Knossos in Crete, which so impressed Picasso and had such an influence on his work, it has been known that the game with bulls is one of the ritual bases on which the ancient Mediterranean culture was erected — a culture to which almost all Europeans are indebted.

Without doubt, it was the people of Iberia, playing with bulls, bullocks, tame bulls and heifers, in the festivals which have always been held in Spain, from the Basque Country to Andalusia, from the Kingdom of Valencia to Extremadura, who were the ones responsible for the fact that here, among us, the miracle of the survival of the fighting bull is an everyday occurrence — an animal which modern human activity, everywhere violating the natural and cultural environment, has annihilated.

From chivalric tauromachy to the modern rejoneo

The progress of the mediaeval war of Reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula was strategically linked to the repopulation of the cities which had been seized by success with arms. It was a period of continual warlike clashes which, from the point of view of military organization, required the constant extension of the units of cavalrymen: the professional cavalry soon became the main nucleus of the army of that period.

On the other hand, tactical demands necessitated the immediate repopulation of the conquered cities and territories. These special circumstances set off large movements of masses in the mediaeval Christian kingdoms. The speed of the relocations and the sheer numbers of the human contingents transferred, combined with the loss of devastated crops, converted the livestock in general, and the herds of bulls in particular, into objects of the highest strategic importance. The historian Sánchez Albornoz recalls that the Chronica Adefonsi Imperatoris refers to many incursions that were carried out by the militias of the councils, from which, when they were lucky, they returned driving immense herds of bulls to their new homes.

Consequently, in those heroic times the bullfight was the happy prelude to surfeit, and in the walled city, before a people that was affronted by hunger and harassed by an implacable enemy, a destroyer of lives, harvests and ploughland, the public exhibition of the skills of the horseriders in their mounted handling of the animals became the most joyful of the nutritive festivals. It was not a case of hunting for sport, but of strategic captures linked to the survival of groups of human beings. And that is how, from its mediaeval origin, the bullfighting festival commemorates the reinstatement of city life, and is, in consequence, an essentially urban event.

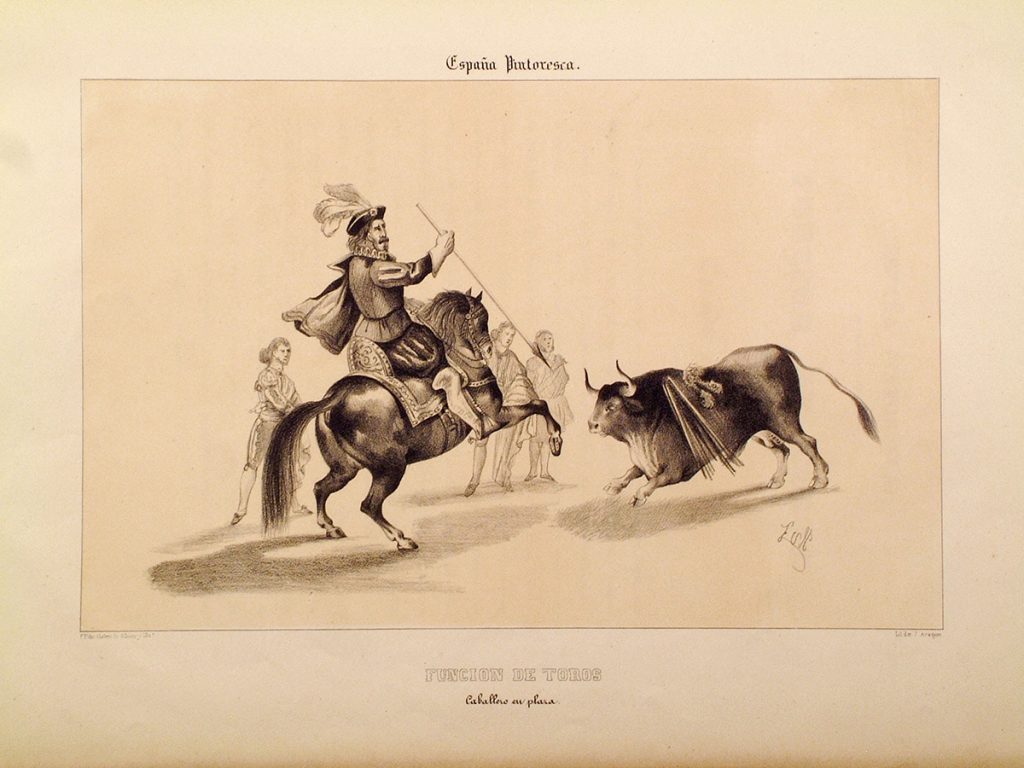

The conquest and division of Seville in the middle of the XIIIth century was also the moment and the place where the first written mentions of festivals of bullfighting on horseback appear. From that time, tauromachy on horseback never ceased to progress and impose itself. If we pause to consult the very rich bibliography of descriptions of ‘festivals worthy of applause’, where games with lances were played and bulls were fought, and which, for an outrageous profusion of reasons, the Spanish city councils organized during the centuries that followed until well into the XVIIIth century, we come to the conclusion that bullfighting on horseback completely dominated the festival scene.

According to Tablantes’ description in his ‘Annals of the Royal Bullring of Seville’, during the XVth century, in the chivalric period, the nobles came out into the bullring richly armoured, displaying on their shields mottos dedicated to the love of their ladies, and with the incentive of appearing worthy of them, brimmed over with fearlessness and bravery in the entertainment of spearing bulls. During that century, in Spanish cities, every socially privileged individual was expected to confirm his hierarchical position by demonstrating in public his mastery of the art of fighting bulls on horseback.

With Felipe IV this festival reached the moment of its highest Baroque extravagance. Having forgotten the restrictive papal bulls, on the occasions of martial victories, royal betrothals, princely birthdays, beatifications, canonizations, enthronements and benedictions, the Spanish cities and towns held brilliant bullfighting festivals. The contemporary art of bullfighting on horseback and sticking lances and banderillas in the bull’s cross is called rejoneo or corrida de rejones. In Spain, bullfighting on horseback was relegated to secondary status in the XVIIIth century, but it continues to be the basic form of bullfighting in Portugal.