Bullfight in Seville

R.M.C.S. Collection

Bullfight in Seville

R.M.C.S. Collection

The bullfight is one of the fairest combats existing in the relationship between Man and the animal world. The Fighting Bull, a race which still exists today because of careful breeding in the fields of the different stockbreeders, is the complete opposite of a domesticated animal. It is raised free in large, open spaces, in the best conditions, so that when the day arrives it can show, in a bullring, its bravery and breeding, aided by its natural fierceness and instinct.

The man, the bullfighter, wins the majority of these loyal battles. He does so by using his intelligence, applying the techniques that he has learned and rationally assuaging his fear, in other words, bravely. This relationship is an inexhaustible source of cultural inspiration.

The bull is endowed with an instinct that is almost unique in the whole of the animal kingdom, that of not admitting defeat. The fighting bull grows during the fight even while it is losing its strength because of the struggle. Any other animal would flee when it saw that it was beaten by an adversary. In his domestication of animals, Man proceeds by overcoming the will and the instinct of the animal, thereby managing to impose a relationship of domination and servitude. With the bull this is impossible, because it does not know the meaning of domination, does not feel pain, and cannot conceive of flight. This is the Fighting Bull.

The historical evolution of this bull/man relationship in a bullring has resulted in its becoming one of the profoundest and most expressive of spectacles. A mystery that may only with difficulty be explained in words, in paintings, in books, in proclamations or in treatises. What it feels like, what it is in reality, can only be understood from the tendidos of a bullring.

In order to understand bullfighting correctly it is appropriate to consider first of all the bullfight to the death, which is the highest expression of modern tauromachy because it has existed since the Art of Bullfighting developed in the XVIIIth century. The Real Maestranza de Caballería de Sevilla contributed, as the Corporation, to the invention of the Art of Bullfighting by designing and building the bullring, with the Caballeros Maestrantes, as lords owning land and livestock, bringing the first fighting bulls from their herds. Thus the Real Maestranza as a whole played, historically, a role that was fundamental in the creation and development of modern bullfighting.

Linked with the earlier bullfighting on horseback and the bullfighting tradition of Portugal, but including many of the principles of the modern tauromachy on foot, are the modern bullfights on horseback, which in Spain involve the death of the bull.

Prince´s Gate. F. Ramos.

R.M.C.S. Collection

Drag of the bull in de bullring in Seville. J.F. Lewis, 1836.

R.M.C.S. Collection

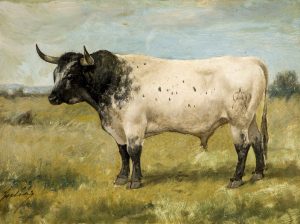

Jocinero, Miura bull. L. Juliá, XIX century.

R.M.C.S. Collection

Bullfights are possible because in Spain the race of wild bulls has not died out, and stockbreeders have been able to select, little by little, from this population of primitive and wild bovines, fighting bulls which are characterized by their possession of two spiritual qualities which distinguish them from the rest of their kind: ferocity and nobility. A ferocious bull is an animal of hard-headed behaviour, which always exhibits an aggressive combativity that impels it to repeat its charge again and again, in other words, to show tirelessly and repeatedly its combative nature.

Bos Primigenius, the primitive urus, is believed to be almost the only ancestral form of the domestic bovines, and which spread its influence by means of strong migrations from the Middle East to North Africa and the south of the Iberian Peninsula, where domestic cattle arrived by two routes: one from the North, with the Celts, and the other via the Straits of Gibraltar. They may have superimposed themselves on other native races, creating the different varieties now found on the Peninsula.

At first, the bulls which were used for the bullfights were those which could not be used for work because of their untameable nature. When the value of the fighting bull exceeded that of an animal used for meat or for working, bulls began to be selected exclusively for the purpose of the spectacles. It was in the XVIIIth century that the raising of fighting bulls as we know them today first began.

For two centuries, the breeders of fighting bulls have been applying a system of selection which today seems normal. At one time it constituted a veritable innovation. In the raising of the fighting bull, consideration is given to lineage when choosing the bulls, and to individual characteristics and progeny when choosing the cows and studs.

Although it is often claimed that, with the arrival of the French dynasty of the Bourbons, the nobles lost interest in bulls, that is far from the truth. It is true that for reasons of Palace etiquette, the nobles stopped competing in the bullring, in accordance with the dictates of courtesy. Many nobles found it prudent to absent themselves from public festivals, and consequently from the main squares of the cities, as they had already done from the Court, and to withdraw to their Andalusian domains and their fields. From that time onwards, they began to take that interest in agriculture which they still continue to demonstrate, in the rural landscape and the beautiful agrarian architecture which, curiously, first took the name of cortijos and later, when the exploitation of the countryside had reached industrial proportions, were called haciendas. In that way, a new economic power was consolidated in the hands of the rural aristocracy.

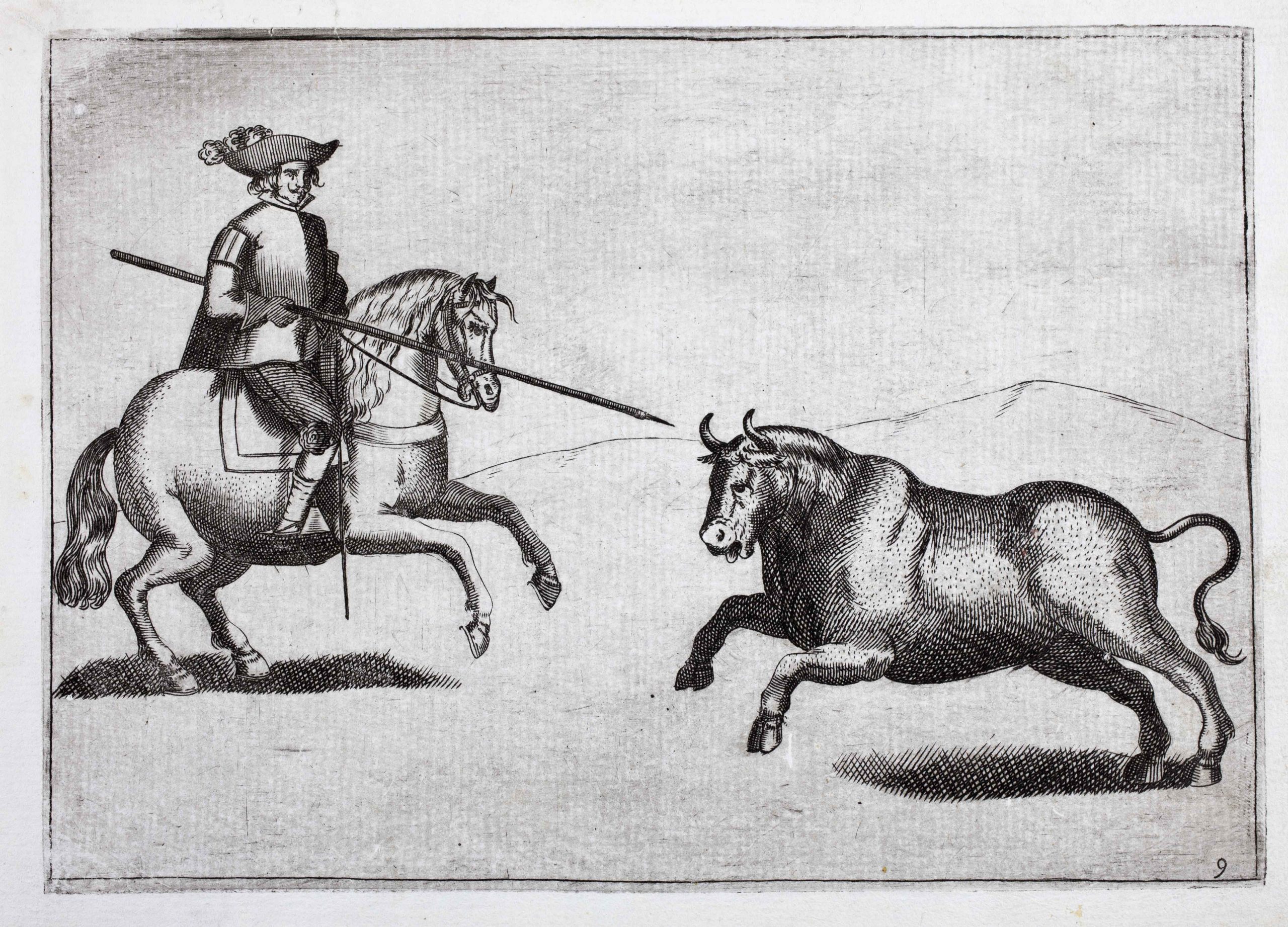

Chevalier pricking a bull. G. Tapia y Salcedo. 1643

R.M.C.S. Archive

Bulls wading through a river. J. Elbo, c.1830.

R.M.C.S. Collection

Toppling a la falseta. J. Díez, XIX century.

R.M.C.S. Collection

Nestor Luján believes that one of the reasons for the nobility’s departure from the bullrings was the lack of horses that resulted from the War of Succession. In the general system of new agrarian activities, the care and raising of herds of fighting bulls shone with a very clear light: into the animal abundance of wild bulls, the nobles would project, as well as their excitement, a large part of their conception of life and death. But there is more: in their strategy to recover the city, the rural nobility found an exceptional ally in the bullfighting festival

The stockbreeders of the bullring of Seville managed to ensure that the spiritual product of bravery acquired a much higher value than the material value of the meat. This was, without any doubt, an unprecedented technical and economic success. It is clear that during the XVIIIth century the Sevillian nobility in general, and the Caballeros Maestrantes in particular, devoted themselves to the raising -selective almost from the outset- of bulls for fighting, and were therefore at the origin of the creation of the Spanish fighting bull.

Harassment and toppling. P. Blanchard, 1835.

R.M.C.S. Collection